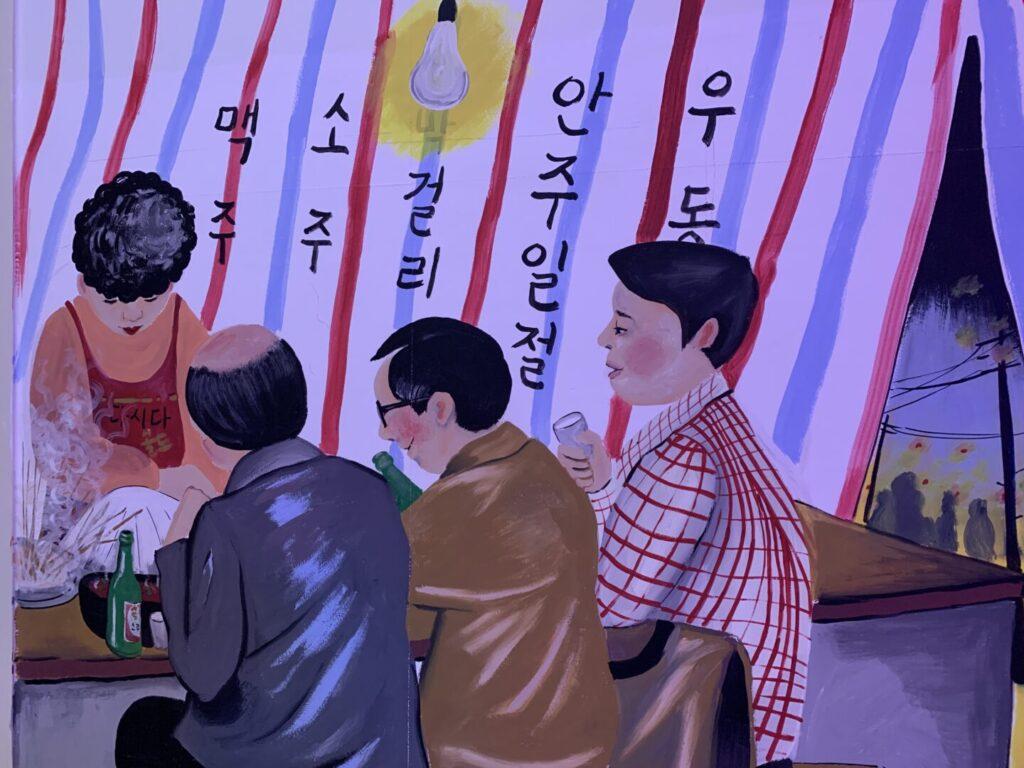

What is Makgeolli?

When people inquire about makgeolli, the simplest and quickest response is “Korean fermented Rice Wine.” Some may also liken it to rice beer. But what makes it such a significant cultural phenomenon in Korea?

It’s akin to asking why wine holds such prominence in Australia, Italy, or France. The straightforward answer lies in Korea’s possession of some of the finest short-grain rice and excellent soft spring mineral water, providing an ideal environment for crafting makgeolli.

Unlike in regions where grapes may lack the requisite quality or sweetness for winemaking, Korea’s fruit wine market is not as robust, despite a slowly growing interest in wines. Makgeolli, steeped in history and enjoyed since the days of the three Kingdoms of Goguryo, Baekje, and Shilla, reached its zenith during the Joseon dynasty.

Much like the ubiquitous home preparation of kimchi, Makgeolli was a drink made in every family’s home.

Makgeolli with its centuries-long legacy, stands as a testament to the enduring cultural preferences of the Korean people. As a milky and subtly sweet fermented rice wine, Makgeolli has transcended time, consistently being a beverage of choice for Koreans.

To grasp the magnitude of Korean traditional alcohol culture, consider that there are approximately more than 600 traditional recipes, each incorporating various seasonal elements, herbs, flowers, and plants—ensuring a lifetime of brewing exploration.

Throughout centuries, even the same types of Makgeolli recipes could taste and smell different and have different brewing methods depending on the family. Among the noble families, there was a significant demand for liquor due to rituals, medicinal purposes, entertaining guests, leisure activities, and tax payments, which contributed to the flourishing of the “Gayangju” or homebrewing culture.

So what happened then?

How did we turn from this unique rice wine to something

overly sweet and cheaply made?

The historical transformation of the Makgeolli industry from a unique form of home brewing to a cheap, mass-produced beverage is intricately tied to Korea’s complex history, particularly during the period of Japanese colonization and the subsequent challenges faced by the country.

In 1916, Japan implemented stricter liquor tax regulations, requiring even households producing homemade liquor “Gayangju” for personal use to obtain a license, subjecting such liquor to higher tax rates than commercially sold liquor. Moreover, they prohibited the sale of homemade liquor to others and prevented license inheritance upon the license holder’s death, effectively aiming to curb homemade liquor production.

By 1932, many traditional and homemade liquors turned into illicit products and disappeared underground due to these measures.

Local traditional alcohol such as Cheongju and Distilled soju began to lose their market position and were maintained only as premium homemade liquors for the elite class and traditional households. At the same time, some traditional liquor companies managed to attract capital investment and establish modern production systems as an alternative to the expensive distilled soju.

The situation worsened for Korea in the 1950s, with the Korean War leading to a shortage of rice supply. In response, the government prohibited breweries from using rice for Makgeolli. This measure resulted in numerous closures and bankruptcies. Some breweries, in a bid to survive, turned to importing wheat from the U.S. and producing Makgeolli from it. However, the use of wheat altered the taste, lacking the natural sweetness and smoothness associated with rice. This marked a critical turning point as breweries began resorting to cheap sweeteners to compensate for the flavor, setting the stage for the commercialization of Makgeolli.

After Liberation and The Korean War

After the liberation, the U.S. military administration was in place for about three years, followed by the establishment of the Republic of Korea government in South Korea. However, both the U.S. military administration and the Korean government showed little interest in traditional liquor. Instead, they implemented strict control over rice distribution and reinforced liquor taxes to improve food supply, stabilize prices, and secure revenue. Additionally, the traditional liquor industry did not improve due to the state of rice supply and market demand during this period.

Amidst the challenges of the early 20th century, traditional liquors faced fierce competition against the more commercialized options. However, traditional alcohol breweries suffered another significant blow during the Korean War, where most of their production facilities were destroyed, and many skilled workers, managers, and successors in the local homemade liquor industry either died or were captured.

Especially affected were premium homemade liquors like Cheongju and distilled Soju, mainly produced and consumed by the old aristocratic families of the region, who were targeted for execution or abduction by the invading forces. Those who survived often faced economic and social downfall during their evacuation, leading to their inability to continue liquor production. Moreover, the extreme wartime economy made it difficult to procure rice, reaching a point where rice could not even be used for brewing.

As we entered the 1960s, although there was some improvement in food conditions, rice production was still insufficient to support the increasing population. With industrialization, the agricultural population decreased while the non-agricultural population, including urban residents, increased. As a result, the goal of food policy shifted towards maximizing agricultural production and distribution efficiency to support the non-agricultural population.

Regulations on traditional alcoholic beverages became stricter, and tax authorities needed revenue from alcohol sales, which led to policies favoring high-profit drinks like diluted soju, lager beer, and cheap imported spirits. In 1965, the Liquor Tax Law was amended, prohibiting the production of traditional alcoholic beverages, including makgeolli, made from grains except for some export products.

Low-quality alternatives like those made from wheat or barley emerged, causing a decline in quality, especially for makgeolli, which lost market competitiveness against diluted soju and beer.

Commercialized Makgeolli

In 1977, improvements in food conditions led to the reintroduction of rice-based liquors. Then, in 1988, with the Seoul Olympics approaching, there was a need to recognize traditional beverages.

However, many breweries persisted in their established practices without making substantial efforts to return to traditional methods. This era represents the point of no return, where the Makgeolli industry shifted irreversibly from its roots in unique home brewing to a more commercially driven, cheaply produced beverage. The historical influences and economic pressures during this period have left a lasting impact on the modern landscape of Makgeolli in Korea.

From the 1990s, regulations gradually relaxed. However, the IMF financial crisis hit the Korean economy, reinforcing the dominance of diluted soju and beer industries. Nevertheless, traditional liquors, which had been overshadowed by grain liquors, began to reemerge, with efforts to restore lost traditional drinks or develop new ones using traditional fermentation techniques. These trends continue to the present day.

As a consequence of historical shifts and economic pressures, the prevailing Makgeolli in the market today is the one that dominates sales across Korea—the aspartame-laden Makgeolli. This version, characterized by the use of artificial sweeteners like aspartame, has become ubiquitous and is widely available in various outlets throughout the country. The introduction of such sweeteners is a departure from the traditional, authentic flavors of Makgeolli, marking a significant evolution in the beverage landscape shaped by historical events and changing economic circumstances.

During the industrialization era, diluted soju became the mainstream alcoholic beverage, while popular drinks like makgeolli and cheongju lost their identity due to the increasing use of Japanese-style ingredients.

Where are we now and Heading to?

In the 2000s, there has been a trend of increasing traditional or modernized traditional Makgeolli made with traditional fermentation methods. At the same time restoration efforts based on traditional documents continue, alongside the development of new brewing techniques.

As South Korea’s drinking culture shifts towards younger generations exploring wine, craft beer, and whiskey, the growing interest in traditional drinks has led to an increase in specialty shops selling distilled soju, makgeolli, and traditional cheongju. Traditional drinks are becoming a new cultural trend, easily accessible for purchase online, unlike mainstream liquors.

Beyond just alcohol, traditional drinks are intertwined with South Korea’s cultural identity, therefore, the South Korean government encourages traditional liquor businesses, offering various benefits compared to other liquors. For instance, traditional liquors enjoy a 50% reduction in liquor tax, making them relatively cheaper.

The Obstacles of Makgeolli and Sool 술

For decades, the market has been dominated—and continues to be dominated—by Aspartame-laden and cheap Makgeolli drinks. If you were to ask an average Korean baby boomer (someone in their mid to late 70s as of 2023), chances are they are unfamiliar with the true flavor of Korean traditional alcohol.

When they encounter craft Makgeolli, one of their many initial reactions is:

- Why isn’t this carbonated?

- Why isn’t it as sweet?

- Why does it have a slight sourness?

- Why is it drier?

- Why is this so expensive?

The prevailing misconception about Makgeolli is that it must always be sweet, a notion that is quite far from the truth. That being said, the exquisite art of traditional craft and home brewing of Makgeolli seems to have skipped an entire generation. Now, it’s not fair to single out all baby boomers or generalize that none of them are familiar with traditional Sool, but this has been the prevailing trend for quite some time.